By Kevin Roberts

If you run a shop, you will need technicians. This article will discuss recognizing, hiring, and managing technicians, including the need for certification.

As mentioned in the previous article, most of us in the emergency vehicle field are aware of two types of techs. There is the old school, experienced “mechanic” who oozes mechanical aptitude (often unrelated to age itself).

Then there is one whose prominent skill is the ability to gain knowledge simply by reading the service information, or, for the purpose of our discussion, can sail through the testing process unfazed by the pressure that the old school mechanic may find overwhelming.

This is an example of an important distinction that is ubiquitous in our society. There are those who mostly learn the principles of their career in school while sitting at a desk (maybe a 70% classroom, 30% lab split). Then there are those who learn the application of their craft by doing, often by trial and error. This generalization need not be fixed or permanent. The student can perform shop practice beyond what is required in school and the mechanic can perform self-study to complement what he learns in the shop. The willingness for each to do so is a character trait that will be addressed in a future article.

As an employer and a trainer of my own technicians for almost four decades, and as a trainer of students for a decade and a half, I am very familiar with both.

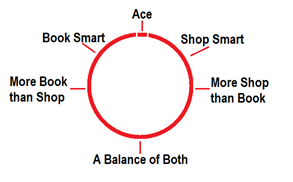

It is important to understand that this is not simply a binary distinction. This is a continuum, and as such, it has a middle and two ends. Most techs vary from each other by where they appear on this continuum. There are relatively few that are completely unmanned by a test, and there are relatively few that can pass a test while offering little or no practical value in the shop. Then there is the ultra-rare tech that can do both well (See figure 1).

Figure 1

Seeing What You Are Looking At

Both student and mechanic must be able to see and process what is before him.

This is a skill that must be developed by the maintenance technician to avoid missing a fault that is not on the checklist. This is also the ability to read and digest (rather than scan) service information. And it is the ability to not miss things when reading a test question.

But it is also a needed skill for the hiring manager. This is the ability to pick up on clues that may be outside of the normal checkboxes when interviewing prospective employees. Important things like potential, emotional intelligence, leadership qualities, and character traits.

To be effective, the hiring manager must not only see the items on his checklist. He must see the potential for growth and the difference between immediate needs and long-term goals. To say this is difficult would be an understatement.

If you are a hiring manager you have probably had, at one time, a prospective employee that you would have hired, “Except for that one thing”.

Was that deal breaker a character flaw? Then “that one thing” was probably a good reason. But we must recognize that in other areas, the person you hire today will almost certainly not be the person you will have working for you in a year. I know very few techs that are today what they were last year. They learn and grow when given opportunity, direction, and accountability.

Certainly, we need many things to allow a shop to function in a professional and efficient manner.

But we need to recognize that it may take the process of working in a shop to produce a proficient tech.

Again, it will not be easy.

As with any other challenge, avoiding a broad-brush approach to decision making may yield positive results.

We could simply establish a rule that to be hired, all techs must be certified; no ifs, ands, or buts. This is understandable due to liability exposure and how certification has a positive impact on it.

However, instituting a universal ban on using non-certified technicians may work against us in the long term.

If we can attract technician candidates who have the proper character traits, then the leadership abilities of the management should be able to produce both individual development and teamwork among the technicians.

I have seen this happen. Perhaps not 100% of the time. But when it works, the results are dramatic.

To train techs to pass a test, when they are not naturally disposed to do so, involves getting them outside (but not too far outside) of their comfort zone. More detail on this in the next two articles. I have seen techs in class rebel against reviewing the English skills needed to pass a test. I have seen those same students surprise themselves and others in the class with their ability to read the question, avoid over-thinking, and recognize the correct answer.

I received this from a student via email in February 2025:

“Yes, I did pass the A-4! Went in with everything you taught us at the class (I did not change any of my answers) and surely passed! Gives me confidence knowing I’m capable of doing the same with the A-5. I sincerely appreciate everything you have done for us teaching for that week. It certainly helped more than you can imagine.”

We have recently seen many changes in our industry. The technician who has dedicated himself to proficiency has recently found himself highly valued by the industry. This fact alone provides an incentive for other techs to dedicate themselves similarly.

It is up to us who have benefited from this dedication to inform and encourage others by our words and our example. The future of our industry depends on it.